Variance Estimation in a Simple Kalman Filter

Consider the following state space model:

\[S_{t+1} = S_t + \epsilon_t \\ V_t = S_t + \eta_t \\ \epsilon_t \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_S^2) \\ \eta_t \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_V^2)\]where \(\{\epsilon_t, \eta_t\}\) are all iid. Given we only observe \(\{V_t\}\) from $t=1$ to $n$, how can we infer both variances?

If the $\eta_t$ noise terms were zero (we can observe the latent states), this would be easily solved by taking the lag-1 difference of $V_t$, squaring each difference and computing the sample mean to estimate $\sigma_S^2$. However with the addition of the $\eta_t$ noise, both $\sigma_S$ and $\sigma_V$ are entangled in the resulting expression:

\[\begin{align} \Expect (V_{t+1} - V_t)^2 &= \Expect (S_{t+1} - S_t + \eta_{t+1} - \eta_t)^2 \\ &= \Expect (\epsilon_t + \eta_{t+1} - \eta_t)^2 \\ &= \sigma_S^2 + 2 \sigma_V^2 \end{align}\]Now we have one equation and two unknowns. The trick is to take the lag-2 difference of the series to derive a second equation:

\[\begin{align} \Expect (V_{t+2} - V_t)^2 &= \Expect (S_{t+2} - S_t + \eta_{t+2} - \eta_t)^2 \\ &= \Expect (S_{t+2} - S_{t+1} + S_{t+1} - S_t + \eta_{t+2} - \eta_t)^2 \\ &= \Expect (\epsilon_{t+1} + \epsilon_t + \eta_{t+1} - \eta_t)^2 \\ &= 2 \sigma_S^2 + 2 \sigma_V^2 \end{align}\]Define $Y_i$ to be the sample mean of the squared lag-$i$ difference:

\[Y_i = \frac{1}{n-i} \sum_{t=1}^{n-i} (V_{t+i} - V_t)^2\]Our estimator is therefore the solution to the linear system:

\[\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 2 & 2 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \hat{\sigma}_S^2 \\ \hat{\sigma}_V^2 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} Y_1 \\ Y_2 \end{bmatrix}\]It is unbiased since $\Expect[Y_i] = \Expect[(V_{t+i} - V_t)^2]$.

The OLS estimator with $k$ lagged differences

It is possible to obtain more equations by taking larger lagged differences of $V_t$. Since this leads to an overdetermined linear system, we use the ordinary least squares estimator to decide the sigmas. The estimator has the traditional analytic form:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \hat{\sigma}_S^2 \\ \hat{\sigma}_V^2 \end{bmatrix} = (X^T X)^{-1} X^T \begin{bmatrix} Y_1 \\ \vdots \\ Y_k \end{bmatrix}\]where

\[X = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ k & 2 \end{bmatrix}\]Like the $k=2$ special case, the general OLS estimator is also unbiased for the same reason. The more interesting question is what is the optimal $k$ to use given $n$ and the population parameters, where optimal is defined here to be the estimator that has the minimum variance.

Variance of the $k$ OLS estimator

The variance is hard to compute for this estimator due to the fact that the $Y_i$ are correlated in a rather complicated way. This stands in contrast with normal OLS regression, where the $Y_i$ are all assumed to be uncorrelated, and the variance of the coefficients estimator would monotonically decrease as the number of rows increases. Here, the optimal $k$ can be thought of as the equilibrium point between two conflicting forces:

- If correlation between successive $Y_i$ is sufficiently low, then having more lags decreases the estimator variance by adding new information.

- The variance of $Y_i$ increases monotically with $i$ because larger lags have more noise terms. This makes the bigger $i$ rows far less useful.1

Here’s the analytical form of the $k$ lags OLS estimator covariance matrix:

\[\Var(\hat{\sigma}^2) = (X^T X)^{-1} X^T \Sigma_Y X (X^T X)^{-1}\]where

\[(X^T X)^{-1} X^T = \frac{3}{k(k-1)} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{4}{k+1} & -1 \\ -1 & \frac{2k+1}{6} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & \dots & k \\ 2 & \dots & 2 \end{bmatrix}\]and letting $i \geq j$,

\[\begin{align} (\Sigma_Y)_{ij} &= \Cov(Y_i, Y_j) \\ &= \frac{2}{(n-i)(n-j)} [g(n, i, j) \sigma_S^4 + h(n, i, j) \sigma_V^4 ] + \frac{4j}{n-j}\sigma_S^2 \sigma_V^2\\ g(n, i, j) &= (n - i) j \left( \frac{(j+1)(2j+1)}{3} + (i-j-1) j \right) - \frac{1}{6} (j+1) j^2 (j - 1) \\ h(n, i, j) &= (4 + 2_{\{i = j\}}) (n-i) + 2 (n - i - j) \end{align}\]Everything except the $\Sigma_Y$ can easily be derived with basic matrix operations. Note the above is valid only for $n > i + j$.

The asymptotic ($n » k$) $\Sigma_Y$ is:

\[\frac{2}{n} \left[ j \left( \frac{(j+1)(2j+1)}{3} + (i-j-1)j \right) \sigma_S^4 + (6 + 2_{\{i=j\}}) \sigma_V^4 \right] + \frac{4j}{n} \sigma_S^2 \sigma_V^2\]Covariance matrix of $Y$ derivation

The derivation uses a number of lemmas:

\[\begin{align} (V_{t+1} - V_t)^2 &= (\epsilon_t + \dots + \epsilon_{t+i-1} + \eta_{t+i} - \eta_t)^2 \\ &= E_{ti}^2 + 2 E_{ti} H_{ti} + H_{ti}^2 \end{align}\]where $E_{ti} = \epsilon_t + \dots + \epsilon_{t+i-1}$ and $H_{ti} = \eta_{t+i} - \eta_t$ are jointly Gaussian. Also,

\[\begin{align} \Cov(E_{ti}, E_{sj}) &= |\{t, \dots, t+i-1\} \cap \{s, \dots, s+j-1\}| \sigma_S^2 \\ \Cov(H_{ti}, H_{sj}) &= (1_{\{t=s\}} + 1_{\{t+i=s+j\}} - 1_{\{t+i=s\}} - 1_{\{t=s+j\}}) \sigma_V^2 \\ \Cov(E_{ti}, H_{sj}) &= 0 \\ \Cov(E_{ti}^2, E_{sj} H_{sj}) &= 0 \\ \Cov(H_{ti}^2, E_{sj} H_{sj}) &= 0 \\ \Cov(E_{ti} H_{ti}, E_{sj} H_{sj}) &= \Cov(E_{ti}, E_{sj}) \Cov(H_{ti}, H_{sj}) \\ &= \min(i,j) (1_{\{s=t\}} + 1_{\{s+j=t+i\}}) \sigma_S^2 \sigma_V^2 \end{align}\]If $A$ and $B$ are jointly Gaussian with mean 0 and covariance $c$ then $\Cov(A^2, B^2) = 2 c^2$. Putting all this together:

\[\begin{align} \Cov(Y_i, Y_j) &= \Cov \left( \frac{1}{n-i} \sum_{t=1}^{n-i} (V_{t+i} - V_t)^2, \frac{1}{n-j} \sum_{s=1}^{n-j} (V_{t+j} - V_t)^2 \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{n-i} \frac{1}{n-j} \sum_{t=1}^{n-i} \sum_{s=1}^{n-j} \Cov(E_{ti}^2, E_{sj}^2) + \Cov(H_{ti}^2, H_{sj}^2) + 2 \Cov(E_{ti} H_{ti}, E_{sj} H_{sj}) \end{align}\]By carefully counting the terms in the double summation we arrive at the variance formula above.

Optimal $k$

From observing the closed form of $\Sigma_Y$ (in the simplifying case when $n » k$), we note that the two variance parameters $\sigma_V^2$ and $\sigma_S^2$ contribute to the entries of that matrix in different ways. In particular, whereas the $\sigma_S^4$ term grows cubically with the lag order, the $\sigma_V^4$ term remains constant. This makes intuitive sense, as each additional lag increases the number of $\epsilon_t$ state-transitionary noise terms, but the number of $\eta_t$ noise terms remains constant. We can therefore conclude that models where true $\sigma_V^2 / \sigma_S^2$ ratio is large have optimal $k$ that is large.

A second observation is that both the $\sigma_V^4$ and $\sigma_S^4$, as well as the $\sigma_V^2 \sigma_S^2$ term, asymptotically vary in $n$ by $1 / n$. Since there is no asymptotically differing impact between the two variance parameters, and the $(X^T X)^{-1} X^T$ does not contain $n$, the optimal $k$ does not depend on $n$.

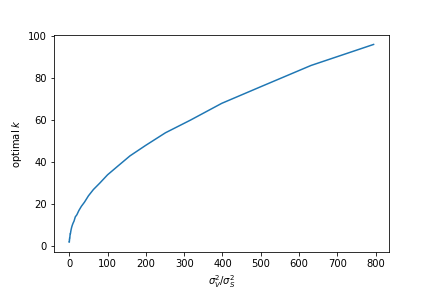

The figure below plots the optimal $k$ of the OLS estimator at varying values of the $\sigma_V^2 / \sigma_S^2$ ratio for large $n$.

It appears this could be well-approximated by a square-root relationship, but I have not yet managed to find a theoretical reason for it.

Generalized least squares

Statisticians have developed the tool of generalized least squares (GLS) for cases when the response variables are dependent on one another. Supposing we know the true covariance matrix of the response variables, GLS fits the coefficients of an affine regression function by minimizing the Mahalanobis distance of the residuals. The optimization problem is:

\[\min_\beta (y - X \beta)^T \Sigma_Y^{-1} (y - X \beta)\]Both OLS and weighted least squares regressions are special cases of GLS, where the $\Sigma_Y$ are identity and diagonal matrices, respectively. An extension of the Gauss-Markov theorem states that GLS is the best (in terms of expected squared error loss of estimated coefficients) linear estimator where the residuals may be correlated.

The problem with GLS in practice is that typically the $\Sigma_Y$ matrix is a priori unknown. To infer it from the data would require first running OLS and then estimating the residual covariance. However, it is impossible to estimate covariance from a single data point (the $i$th and $j$th residuals of the regression data), so the practioner must specify some special structure to the residual covariance matrix, such as it being low-rank or diagonal.

Fortunately in this case, only two parameters are needed to obtain the residual covariance matrix, $\sigma_V^2$ and $\sigma_S^2$. This lends itself to an iterative procedure that alternates between computing the residual matrix from the latest variance parameters and running GLS using the estimated residual matrix to estimate the variance parameters. For the first GLS, one may use the identity matrix as the residual covariance matrix. This is an instance of the general method known as feasible generalized least squares.

Convergence of feasible GLS estimator

Variance of feasible GLS estimator versus OLS

-

This opens up another interesting question of how the rows might be weighted so as to give precedence for the smaller $i$ rows in computing the estimator. ↩

« The Brownian Bridge Joint Max Position Distribution

Varying Coefficient Models Via Gaussian Process Priors »